Right Temperament:

Living with Luangta Maha Boowa

by Ajahn Dick Sīlaratano | June 6, 2020

Ven. Luangta Maha Boowa, a direct disciple of Ven. Ajahn Mun, was one of the most venerated teachers of twentieth-century Thailand. Considered the leader of the Thai Forest Tradition for many years, he was known for his fierce teaching style.

One morning, several months after my arrival at Wat Pa Baan Taad, a Theravada Buddhist monastery of the Thai Forest tradition, I stood at the railing of the main sala waiting for the monks to begin their early morning alms round. We had just finished our cleanup duties and put on our robes in preparation for the walk to the village. Our teacher Luangta Maha Boowa, who would be leading us on alms round, was there giving the monks instructions and admonishing them as usual. I, meanwhile, stood with my eyes closed meditating, inwardly focused and disengaged from my surroundings. I had been a monk for several years by that time, and meditation was my life. It was the activity that I prized above all else. I considered myself diligent in my practice and was pleased with my results. After all, meditation was what Buddhism was all about. Or at least that was what I assumed at the time.

Suddenly the sharp crack of Luangta’s voice broke through my seemingly blissful reverie. I opened my eyes to find him pointing a finger directly at me and exclaiming something in a loud voice to the senior monk next to him. Because the conversation was in Thai, and I was not yet fluent in the language, I did not understand the meaning of what was said. But I knew it pertained to me, and that got my attention. I soon found out that Luangta had ordered me to begin doing the early morning duties at his kuti starting at dawn the next day. I was to join his two regular attendants to observe in detail everything they did and to be mindful of how they conducted themselves in order to replicate those duties when called upon. Thus began my formal education in what Buddhism was truly about.

In my early years in the robes I dutifully performed the chores required of a junior monk while being somewhat resentful of how those tasks limited the amount of time I could devote to meditation. I fulfilled those responsibilities efficiently but grudgingly, as though I could not spare the time. But soon after my new duties began, the hours spent serving as Luangta’s personal attendant became the central focus of my life and the inspiration for my meditation.

Several months later, the other two attendant monks departed, and I inherited their combined duties. Attending to Luangta was demanding and time-consuming, requiring a persistent attitude of vigilance and self-sacrifice. The training was tough, but this toughness forged strong character traits that gave me the inner strength needed to face the hardships of monastic training. Even though I was following a monastic lifestyle, it was difficult to divorce my mind from its deeply ingrained thought patterns and value judgments. Strong inner qualities were required to overcome these tendencies – qualities I had to find within myself. Luangta’s uncompromising training methods provided me with the means to realize for myself the power inherent within my heart – the power to stand firm and work things out with perseverance and determination.

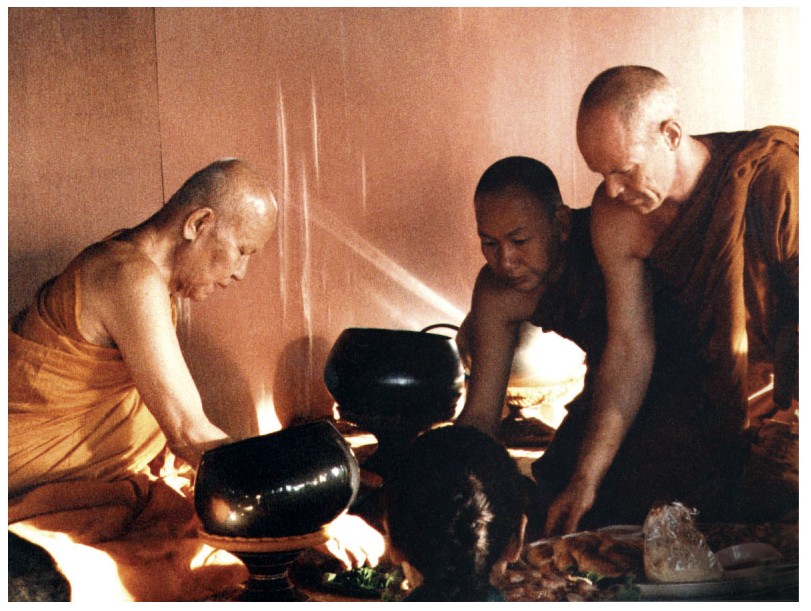

Helping serve the teacher at the meal and receiving their bowl afterwards represent just a few of the many duties a junior monk might perform.

Helping serve the teacher at the meal and receiving their bowl afterwards represent just a few of the many duties a junior monk might perform.

Each morning, I approached Luangta’s kuti in the half-light of dawn and began polishing the hardwood floorboards of its wraparound veranda. Down on all fours, gripping two coconut husks with my hands with one under each palm, I pressed them to the floor and rotated them vigorously as I crawled from one end of the veranda to the other and back again. The veranda had three sides and all of them were long and wide. The skin on my knees grew heavily calloused over time. After polishing them, the floorboards were swept of dust, the toilet was scoured and mopped and the bath water was topped up. All these tasks were completed before Luangta emerged from his room. After hanging out his bathing cloth to dry in the sun, I swept his room and wiped down the floor then collected his bowl and robes and carried them to the sala, where I had his robes ready for him just in time before he arrived.

After returning from our alms round in the village, where food offerings were mostly lumps of sticky rice, all the monks immediately set about ladling out portions of cooked food from large pots into their alms bowls – except for me. Luangta had assigned me a different chore during that time. Upon returning, I had to quickly collect spare lumps of sticky rice from the monks’ bowls and put them on a large tray that was reserved for feeding the squirrels in the forest behind Luangta’s kuti. Because Luangta insisted that the squirrels be fed in a timely manner, I had to rush off at once to place large lumps of rice at designated feeding stations which were located in various places throughout the forest. There were three feeding stations in Luangta’s section of the forest, each one farther out than the preceding one, which meant that I had to be swift in order to return to the sala before the meal began. On most days, this meant that I had to run along a narrow forest path, evading tree roots, stones and fallen branches in order to quickly unload my cargo at each station. Afterwards, I would hustle back to the sala, just in time to throw on my robe and sit down in my assigned place as Luangta started to chant his blessing. I was usually drenched in sweat by the time I started eating.

I ate quickly, finishing my meal before everyone else so I could put my bowl outside and return in time to receive Luangta’s bowl just as he finished eating. Having washed his bowl, dried it in the sun and put it back in its case, I took his robes from the clothesline, folded them neatly and returned them with the bowl to his kuti.

Each day after the meal I straightened up Luangta’s kuti, put away his bowl and robes, tidied his bedding, arranged his sitting cloth, spittoon, kettle, tooth sticks and fly whisk, and made sure his other robes were either put away neatly or hung out in the sun to dry. I had to have everything in order before he returned from the sala and entered his room. If something was out of place, or not in the proper order, he scolded me with a pained expression on his face, even though he never actually told me what I’d done wrong. I was expected to intuit my mistake from careful observations, factoring in changing conditions like weather, time of day, specific circumstances of the moment and a general reading of his expectations. Thus, the proper order was a constantly shifting objective that might vary significantly from hour to hour or day to day. The best solution was to learn to think like Luangta did and try to perceive the situation as he would in that moment. That specific challenge inspired me to adjust my habitual ways of thinking and behaving to conform to his lofty standards by relying on attention to detail and enthusiasm for reasoning things out.

I soon realized that Luangta firmly believed that the training must be difficult and challenging enough to force his students to develop the kind of temperament needed to overcome the innate human tendency towards indolence and self-absorption. When jobs were well done, Luangta showed no reaction; he gave no praise or pat on the back. He remained impassive. He refrained from offering positive feedback, as though he expected nothing less of his students. When a mistake was made due to a misunderstanding, his reprimand tended to be mild. But mistakes resulting from carelessness or indifference were met with a sharp rebuke. In his reprimands, Luangta was not addressing the student personally so much as he was rebuking the defilements that had taken over that monk’s heart and clouded his mind. The more insidious the defilements on display, the fiercer was his response. Lapses in attentiveness were not tolerated, even with the smallest things. Nothing was to be considered so insignificant that it could be casually overlooked. Every aspect of a task was important.

Attending to Luangta presented me with an incredible opportunity, albeit one that required much skill and effort. It challenged me to relearn everything I thought I knew already. His exacting standards forced me to be very observant and circumspect at all times. He trained me to develop a science for everything I did – hanging out robes, taking them in, folding them, setting out sitting mats, arranging bedding and performing routine cleaning chores – and to give everything I had to the work. That included a broad awareness of the cause and effect implications of all my decisions. I had to give myself wholly to every task with no half-heartedness or complacency, otherwise, he would scold me for being negligent. Whenever that happened, I just had to accept it and refocus my attention anew. Through these experiences, I learned to accept Luangta’s judgments and admonitions without objections. I simply picked myself up and dutifully carried through with the task at hand, without discouragement or complaint. I undertook every task he gave me with that kind of resolve, regardless of how difficult the challenge seemed. With a firm belief in my teacher, I made the effort to figure problems out for myself.

Luangta believed that a monk needed to be able to handle pressure and stress in the training. That was the way he himself was trained by his teacher. The intensity of the training squeezed my defilements until they had nowhere to hide, forcing me to confront them head-on. If he thought I could handle more, he increased my responsibilities to test the limits of my capacity to cope with stress.

One task that I took considerable pride in was making sure his veranda floor was polished to a fine sheen. That was the space where he often sat and received guests. In the hot season, when the temperature often reached 100 degrees Fahrenheit or more, the hardwood planks on the veranda absorbed the ambient heat. Luangta’s preferred method for drying a wet bathing cloth was to stretch it out flat on the floorboards to allow their heat to dry it. A wet robe drying on the floor tended to leave water marks on a polished surface, which took a lot of extra scrubbing to remove. This inconvenience became a mounting source of frustration for me. Why not simply hang it down from the veranda railing like everyone else? It would dry just as quickly and save the extra work. But when I suggested that option, he was adamant that a wet robe must be dried on the floor, as though only a fool would think otherwise. Since I was not about to let go of my determination that the floor look its best, I was left with no alternative but to scrub those areas even harder every day.

By extension, the belief that every wet robe had to be dry and ready for his use in a timely manner became as important to me as the polish on the floor. On rainy days, this meant bringing his wet robes to the fire shed to dry them thoroughly by the fireside. I learned to perform all my chores with this same commitment, as though that was the only right attitude to take.

Using my time wisely by being of service to my teacher and the monastic sangha proved to be a great benefit to my spiritual progress. Performing such wholesome deeds provided a fertile ground for planting and nourishing many virtuous qualities in the heart while also strengthening the virtuous roots that had been cultivated in the past. Building up strong character traits in that way fostered a spiritual temperament that was worthy of having more beneficial opportunities open up for me as my commitment to the path deepened. This attitude towards spiritual practice gives rise to an increased sense of inner worth, which is an important but often overlooked reward of Buddhist practice. Bolstered by that inner wealth, we are more likely to encounter favorable causes and conditions in the practice, both now and in the future.

Sometimes the favorable causes and conditions that lead to spiritual growth defy our common-sense expectations of what “favorable” means. For my first seven years serving as Luangta’s attendant, he scrupulously avoided traveling to Bangkok. Later on, some lay supporters offered him a sangha residence built on land at the very outskirts of metropolitan Bangkok where he could live in relative seclusion yet still be available to teach his students in the capital. From that time onward, I traveled south with him several times a year to take up residence near Bangkok for two to three weeks. Besides me, he always brought along a third monk. This monk had an aggressive and unruly temperament. He was known to be a troublemaker, and he was constantly in my face. He acted more like a rival than a friend and rarely missed an opportunity to publicly show his contempt for me.

At first, I could not understand why Luangta brought this contentious monk along for the journey. I assumed Luangta was concerned that if he were to leave him behind, the monk would cause trouble at the monastery in his absence. In any case, his presence in Bangkok made my life very challenging. He goaded me with verbal and at times even physical confrontations which were intended to provoke an angry reaction. The less I reacted the harder he persisted. Early on, I resolved that out of respect for my teacher and out of gratitude for the opportunity to be his attendant, I would discipline myself to maintain the decorum expected from a member of the forest sangha. I was determined never to compromise that discipline regardless of what conditions might arise.

This monk’s hostile behavior pushed my resolve to its limits. There were many days when I stepped onto my meditation path and paced back and forth for three or four hours in an effort to calm the emotions that I kept tightly under control during such encounters. In the beginning, just keeping my anger inside and not allowing it to express itself in speech and action was a real struggle. But I knew that Luangta expected no less of me. I soon realized that he expected a lot more; he expected me to use the verbal or physical abuse of my external enemy to turn the tables on the internal enemies of anger and hatred in my heart. That was the reason he brought the quarrelsome monk along in the first place.

Bottling up anger and remaining unperturbed in the face of painful feelings was a necessary first step, but understanding how to subdue and overcome destructive emotions in all circumstances was the ultimate goal. That required incorporating dimensions of awareness like wisdom, perseverance, patience and dispassion to pry open the heart and shed light on its full range of mental activity – both the good and the bad, the skillful and the unskillful, those which lead to happiness and those that lead to suffering – and thus perceive things as they actually are without distortion.

After all, his angry behavior was the product of the defilements in his mind. Why should I resent someone who is the victim of his own defilements? Should I not feel sorry for him instead? By acting on the impulse of the anger in his heart, he was just creating further causes for his own suffering. Knowing this, what purpose would my anger serve? Would it not merely create further causes for my own suffering?

Instead of seeing my adversary as an enemy, I began to realize that his aggressive behavior could teach me a valuable lesson that would help my heart cultivate enduring virtues. Although contending with him was a bitter experience for me at the time, looking back now I can appreciate how that monk was a helper on the path of practice. By showing me the reality of my own defilements, he provided opportunities for me to develop the patience and strong resolve needed to counteract feelings of anger and hatred in my own heart. Had Luangta not thrown me into the lion’s lair, I may never have cultivated the virtues needed to turn the pain of an angry heart to my advantage.

Luangta’s medicine could be bitter to taste, but it was an effective cure for the heart. I spent many years training under the influence of his bitter tonics. Luangta always acted as if he expected me to work things out for myself. This meant that no matter what demands he made of me, I had to somehow fulfill them. Through dogged effort, I began to realize that I had powers of perception and discernment that I never thought I had. Gradually, I learned to avoid placing limits on my own ability.

That kind of mindset characterized my service as Luangta’s attendant. It was not due to reasoning so much as to actual experience that I was able to persevere through his training despite my shortcomings. That training provided me with the means to recognize an inner strength that empowered me to stand firm and work out things for myself with perceptiveness and determination. For his part, Luangta’s emphasis was placed squarely on temperament – on those dimensions of human character that open the way to goodness, ease of progress and spiritual prowess. Attending to Luangta was like gathering provisions for the journey of the heart – spiritual resources like renunciation, wisdom, effort, patience, resolve, truthfulness and dispassion, which are invaluable assets for the pursuit of liberation.

Luangta believed that the right temperament was just as critical to success in practice as were intelligence or effort, if not more so. Only by raising the character of our inner being does the mind become worthy of encountering the right circumstances, the right guidance, and the right insights that will lead to realizing the truth of Dhamma. The practice requires more than simply an emphasis on striving for deep samadhi and insightful experiences. Actually, the level of meditation a person is capable of achieving is dependent on an inner readiness to access that level. For that reason, cultivating our inner worth is a critically important, though often neglected, aspect of the overall practice. This principle is surely the most significant lesson that I took away from Luangta’s approach to teaching his students.