Becoming Fearless:

Loving-Kindness Meditation

by Khenmo Drolma | July 1, 2020

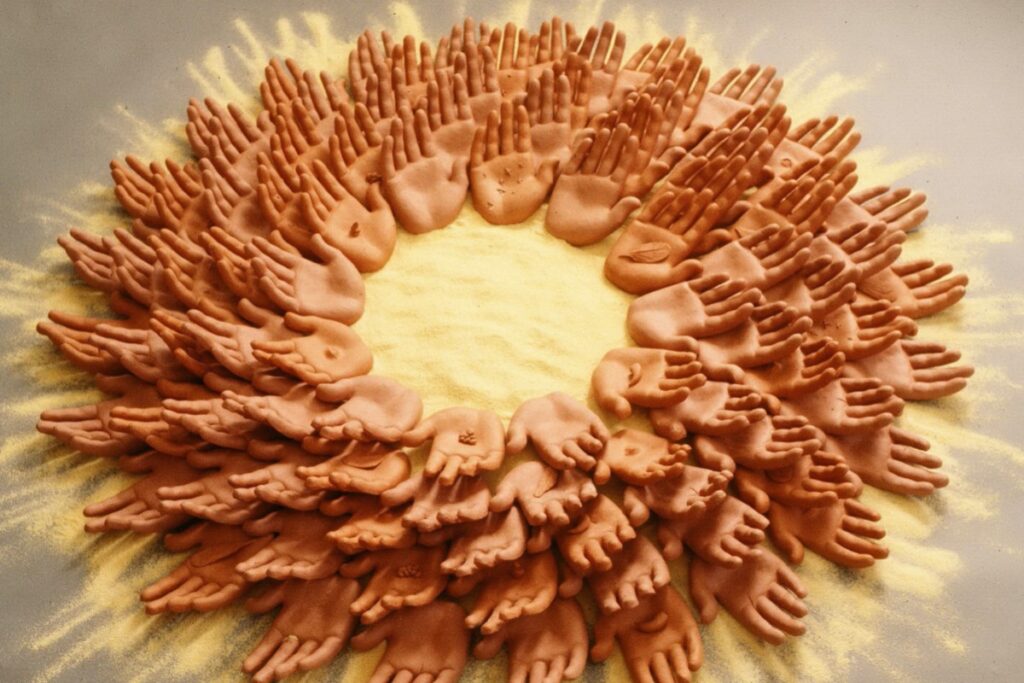

“Quan Yin” is a sculptural expression of compassion that Khenmo Drolma created while she was being treated for cancer in 1993. Traditionally Quan Yin, the deity of compassion, is pictured with 1000 hands to hold medicine for those in need.

“Quan Yin” is a sculptural expression of compassion that Khenmo Drolma created while she was being treated for cancer in 1993. Traditionally Quan Yin, the deity of compassion, is pictured with 1000 hands to hold medicine for those in need.

Thirty days into a five-month, solitary retreat in India, I received a message saying that my brother had been murdered. The monk who brought the message drove me down the mountain to make a phone call to my family and then returned me to my room. Such retreats represent a solemn promise; one is to maintain silence and may only leave one’s room in order to receive food. As the funeral had already taken place, I made the very difficult decision to complete the remaining four months of my commitment. I was left alone with this shocking news and, of course, could not go on as normal. Instead, I cried.

Even before becoming a nun, I had taken a vow to exclude no one from my heart. The prayer I said at the beginning of each day — to love my enemy — began to take on new meaning. I had to learn how to love my brother’s murderer or break my vow. It felt like torture. A simple meditation on loving-kindness became my whole practice. First I summoned the feeling of kindness, then I extended it person by person as far as I could. I sought to touch kindness just to feel something other than anger and grief. To summon that feeling, even for a few seconds seemed impossible. My mind would fly to my brother lying alone dying, having been shot for a few dollars, or to my mother who was in tremendous pain. With no other refuge, I began to reteach myself the Dharma and entered into a deep exploration of the special Drikung loving-kindness meditation.

First, I sat, visualized my spiritual teachers, and experienced their love so that I could recall the taste of kindness. Knowing their dedication to all beings, I reflected upon the vows that they held impeccably and had passed to me. I contemplated what it would feel like to love whoever came to mind equally. A stranger to these monks, neither male, nor Tibetan, I was a recipient of their great care and kindness. I prostrated to the altar and studied the statue of the Buddha with his visage of equanimity. It is our practice when doing prostrations, to imagine our enemy standing in front of us. I imagined the Buddha’s perspective gazing out at sentient beings, loving me and also loving the murderer equally. I kept prostrating and then sitting, considering the reality of this application of the Dharma, loving one’s neighbor as oneself, loving the enemy. I began generating heartfelt kindness, gathering it, filling an internal reservoir. Over time, I began to let go of my own grief and to extend loving-kindness to my brother and to my family. I still was unable to even think of my brother’s killer. After some weeks, the killer began appearing in my imagination on the edge of a crowd. I continued sending kindness to my family, colleagues, neighbors, and strangers, but the flow would stop cold as my mind touched upon the thought of the murderer. Over and over I began again.

Close to despair, I had a dream. In it, my teachers were beside me holding me with love and encouraging me. Step by step, they showed me the way. If I could see their nature as pure, their immense loving compassion developed through the same meditation training I was practicing, then it was possible for me to become like them. If I believed that our minds were of the same nature, and trusted all minds had potential for loving-kindness, then it must also hold true that the murderer had the exact same seed and potential as I had, as they had. Not meeting the Dharma or kind teachers, his heart had hardened over time with anger. Every time my mind lost the capacity to hold and send loving-kindness, I returned to the beginning and rested again in the feeling of my teachers’ radiance. Then, once again, I allowed it to flow outward. I alternated between cradling my brother in kindness and glancing at the murderer. I continued this way for some days and then, one day, the killer was no longer there. Instead, in his place there was a baby! In my mind, whatever caused him to become a crazed drug dealer was gone and, in his place, I saw the lovable child within the outer shell of anger. I could see his beauty. My brother floated away, both of us at peace. Anger was released, the weight lifted. I had immense gratitude to my teachers, and for this profound practice as well as the circumstances necessary to patiently conduct such depth of practice.

Khenmo Drolma with her teacher, His Holiness Drikung Chetsang Rinpoche, head of the Drikung Kagyu order of Tibetan Buddhism.

Khenmo Drolma with her teacher, His Holiness Drikung Chetsang Rinpoche, head of the Drikung Kagyu order of Tibetan Buddhism.

The Drikung Kagyu lineage, founded by Jigten Sumgön (1143– 1217), offers a balanced and structured training that helps us soften and expand our hearts. In our lineage, we begin every activity with an aspirational prayer of bodhicitta, loving-kindness: May all mother sentient beings, especially those enemies who hate me, obstructers who harm me and those who create obstacles on my path to liberation have happiness, be separated from suffering, and quickly be established in the state of perfect, complete and precious Buddhahood. We set an intention to benefit all beings and acknowledge that this includes the difficult people in our lives. Some days it is difficult to say this prayer sincerely, especially when we are in pain ourselves and simply wish to relieve our own angst. With this opening prayer we hold in our mind the view that pain is not to be avoided, but seen for what it truly is: habits and patterns of mind that can be slowly eliminated. Every effort, however short and imperfect, strengthens our intention to open our hearts. This intention reminds us what it means to be all-inclusive in our altruistic wish.

The word for meditation in Tibetan, gom, simply means familiarization; we wish to become familiar with our mind and uncover its true nature. We learn about how our minds function so that we understand the frail and vulnerable human nature that we share with all beings. The accrued wisdom helps others. Great kindness and compassion, or bodhicitta, is not a personality trait, greater in some and lacking in others. It is a product of consistent mental training, developed in much the same way as our physical strength is improved through going to the gym. Nor are there limits to bodhicitta. We can learn to open our hearts to everyone as if they were our most beloved child, even our enemies.

For some, meditation on kindness can immediately highlight a narrowness of heart and we are shocked that we are not who we would like to be. We tend to flee from this insight, and are often faint of heart when sitting with our thoughts because we know only too well that many of our mental states are painful. We have to want to see how our ignorance works so that we can uncover the sources of our suffering. Self-hatred or denigration sends us running in the opposite direction. To become fearless, I first had to become friends with the whole range of thoughts and emotions inhabiting my inner world. Learning to approach my mind with an attitude of gentleness without judgment has changed my relationship to meditation. The most vital lesson I have learned is that my mental habits of inner harshness, shaming, and guilt absolutely inhibit authentic compassion developing, while curiosity and friendliness promote transparency and growth in kindness.

Lord Jigten Sumgön’s instructions for developing loving-kindness are deceptively simple. First, we sit in the posture of the Buddha and smile. We cultivate the feeling of loving-kindness, train in strengthening it for some time, and then let it overflow boundlessly into the ten directions. The important nuance in his instruction is the directive to begin again whenever the depth and intensity of our loving-kindness falters. When we encounter a being we cannot love wholeheartedly, we begin again, contacting and strengthening loving-kindness itself.

The training instructs us to steep ourselves in the feeling of kindness by visualizing someone for whom we feel a deep, uncomplicated loving-kindness, or from whom we have received loving-kindness. To help, we are advised not to visualize someone we are very close to, such as our partner or, for Western students, our parents, as the complexities of such relationships can hinder the clarity of the feeling. Instead, we are invited to bring to mind someone who evokes in us feelings of delight and joy such as our spiritual teacher or a laughing baby. As we remember an experience of a child walking toward us, we are often able to connect with a spontaneous open feeling of unconditional love. We may be able to bring up a memory of an instance when we were the recipient of someone’s goodwill — a moment involving a significant teacher, for instance. Or we may discover that we have so many boundaries surrounding our heart that it is difficult for us to evoke the smallest feelings of loving-kindness. It can seem like a painful search, especially if we judge ourselves lacking. Noticing this and letting go of any inner criticism, we can encourage curiosity; puppies, kittens, even plants can bring up tender emotion. For many, the recollection of nature, sunlight on our skins or being held by the ocean as we float, can generate wonderful feelings of openness and joy that can be used as a starting point for loving-kindness to arise.

Once contacted, we focus on the feeling of kindness and drop the story. We smile naturally and experience warmth flowing through our bodies as we relax. Lord Jigten Sumgön’s instructions tell us to use this feeling of loving-kindness as our object of concentration every day for at least two weeks. We want to get to know it in our bones, play with its subtleties, and recognize its fine resonances. Then we gently expand it in radiating spirals. We may begin extending it outwards from the heart in any way that is comfortable, visualizing it spiraling out to our circles of friends and family or even traveling door-to-door in our neighborhoods.

This mental openness can seem uncomfortable, even frightening at first. When we try to extend loving-kindness to another with no defenses or boundaries, fear can instinctually arise and shut down the flow of warmth as if a door were slamming shut. The strength of our fear can seem shocking. We must recognize this as the beginning of a profound journey. First, we must attend to our physical and psychological safety. Then with gentleness we investigate: How strongly and sincerely can we feel this loving-kindness for our families and coworkers, for strangers? How have barriers in our hearts arisen and how are they dismantled wisely? What does it feel like as its energy begins to wane? What is the first sign of its shutting down? After spending some time exploring how to generate, and stay with, the feeling of loving-kindness, we move from the easier people in our lives, to strangers and eventually to those who have harmed us or with whom we have issues. We wish to see where we are limited and why. This means we want to know all the dark corners of our minds in order to dismantle the walls pain has created. Every time the feeling of kindness is weaker than what we have generated in previous meditation sessions, we go back to the first stage of becoming familiar with the feeling and strengthening it again. We become sensitive to the slightest nuance of fluctuation, returning to the source for strength.

Each meditation session spent in the exercise of loving-kindness allows different kinds of beings to arise in our minds. It’s not difficult to think with kindness of those we love, less so of those we don’t know, even if they seem similar to us. We slowly understand that when we pray for “all sentient beings” we are welcoming absolutely everyone. As we increase our willingness to make effort, and as our minds feel safer, we become ready to explore our most fearsome shadow regions. I still occasionally need to remind myself how to soften inner harshness when obstacles arise. At a fundamental level, many of us feel that there is something broken inside; that we have an unnamed and unidentified wound that will take over. We may not become aware of our pain until we become quiet or sit to meditate. The simple fact is that we all have pain just below the surface simply because we are human. We meditate to see what humanity is. To cultivate friendliness, I imagine my mind as an old friend with whom I’m meeting for coffee. When I join dear friends for coffee, I do not judge them. They might tell me anything and I would be there to listen and help. I have learned to approach my meditation sessions similarly, becoming a steadfast, gentle witness to my mind.

The Buddha used practical, earthy images in explaining the difficult process we encounter when we work with our emotions. He once said that overcoming anger was like a snake shedding its skin. That excruciating slow, painful, peeling cell-by-cell characterized my experience of calming anger towards the murderer in my retreat. I have had to learn resolute patience with the process of untangling difficult emotions more than once. My mind contains all the disturbing emotions that I criticize in others. In the loving-kindness meditation, every meeting with “enemy”, the unlovable, the stranger, is the beginning of an untangling process through which my mind creating “other” becomes more visible and my part in the dance clearer.

We are the only ones who can liberate our own hearts. Fearlessly observing our minds, we are able to see clearly that we are those truly harmed by maintaining anger and the thought of “enemy.” Every time we conquer our barriers and their underlying compost of emotional baggage with loving-kindness, our heart expands in wisdom. We understand others’ minds by understanding our own. We are rewarded with confidence in the Dharma’s truth and an increasing capacity to help.

Over time our enemies truly become our teachers. Working with all that arises, uncovering and welcoming the afflictive emotions, we dismantle the walls of our heart. In maturation, this meditation can become a doorway to the absolute. No enmity without, no aggression within; I and Thou recede into emptiness. Our loving-kindness can expand to the whole region, the entire country, and the whole planet effortlessly. We have the potential to visualize it traveling limitlessly to all ten directions, in “the three-thousand world system.” Without exception, we can perceive all sentient beings as our kind mothers. Our hearts are one with the Buddha and we truly become a lifeline for those stranded in despair.