War & Peace I: Billy Fitzgerald’s Journey from Gang to Military to Monastery

by Tan Nisabho | Nov. 29, 2021

After escaping the violence-ridden neighborhood where he grew up by joining the British Army, Billy encountered experiences during the Northern Ireland Conflict which left him with severe PTSD. The resulting depression and chronic addiction led him to eventually seek refuge at Amaravati Buddhist Monastery outside of London. His subsequent healing, work at the monastery, and reconciliation with former members of the IRA show the power of the Buddhist path and the importance of the Sangha which carries it forward. The below text was drawn from interviews conducted in 2018.

I was born in Liverpool, England, and I come from a very violent background. Walking down the street, it was gangs. In the house, it was violence. And there were killings. There were two killings before I was a junior. I didn’t do it, but the gangs I was involved with did. The gangland—I wasn’t suffering from paranoia, but just sheer survival instincts. As a kid, I was stabbed in the head, beaten, dragged across the floor by my hair, kicked.

I didn’t look to my father for lessons. He was part of the suffering. He did teach me not to back down—to be rough and tough. And my dad was a hard man; he was a laborer.

My mother was a sick woman. In retrospect now – sick emotionally and sick physically. I always say, “Hurt people: hurt people. Who hurt the people who hurt me?” I was scared of her. She died of leukemia when I was twelve, so that was that. At a very early age, I learned to do shopping, how to manage a house and things like that. We lived in extreme poverty—there was just enough food on the table.

Religion was part of it – Catholics versus Protestants. I was brought up a Catholic. One part of Liverpool was Protestant and the other area was Catholic, and they had statues in the windows showing what they were. If you walked into the wrong part, there was trouble. It was mad, crazy—there were no guns that time, but there were plenty of knives, axes, and hatchets— plenty of violence. You couldn’t walk down the street without being part of a gang. I was part of armed robberies.

How was school?

I felt grossly inferior to everybody and was told I was ignorant. I asked my mother what that meant, and she said, “You’re thick, stupid, and know nothing.” So, I grew up thinking I was thick, stupid, and knew nothing, and I just stopped trying in school. I just argued, and got the lowest grades each year.

Was there anyone good?

My auntie Maggie. She let me know that there were good people in the world. I went to stay with her when my mom was in the hospital, and it was fantastic. There was no gangland stuff, no… I just knew I was safe and secure and I was so sad when I had to go back to my neighborhood. She was brilliant. She showed me kindness. She looked after me—took me to the circus and took me to the park. When I left her, I went back to my birth parents, and that just didn’t happen. There was violence, sexual abuse, and I felt totally out of place there. It was horrible. But Maggie looked after me. We played with toys – she used to hug you and things like that, And I didn’t get that with my birth parents. I just loved her.

There was this one time after I left, I was at a wedding party with my mother, and I picked up a drink and it splashed on my shirt, and my mother attacked me in the middle of this wedding, and Maggie grabbed her and said, “Don’t you ever hit a child like that. Don’t you ever do that.” She held me close. I felt bloody protected by Maggie, y’know?

When my mom was very ill, I didn’t go to school for the last two years. I was busy looking after my sister—washing, cooking, cleaning, and so on. I loved her, and I felt like her dad. Then social services took her off us, and that broke my heart.

That’s when I ran away and joined the army.

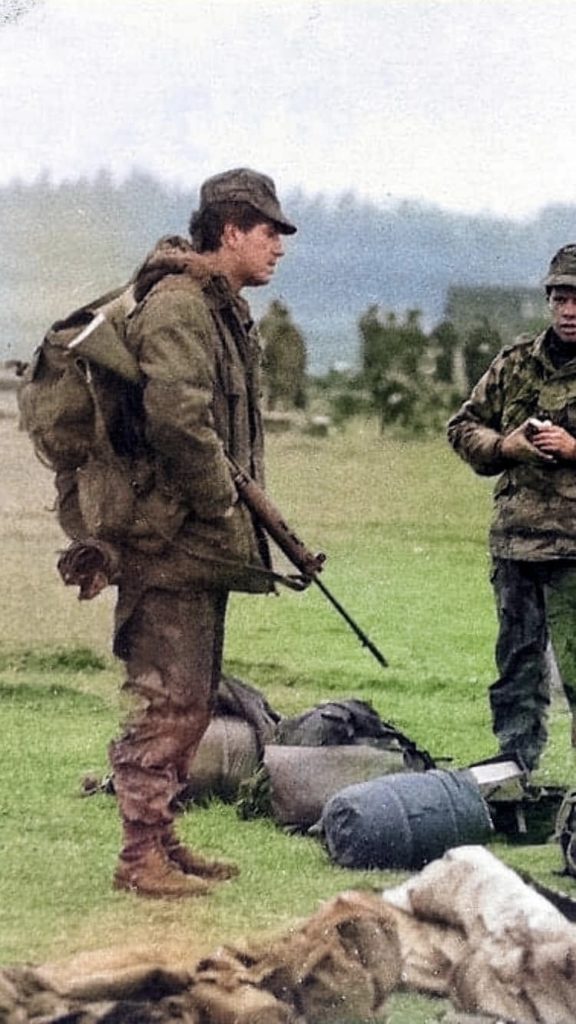

I was in the army for two years fighting terrorism, and it was just madness—absolute madness. I developed PTSD to the point where I was afraid of going out, afraid of walking down the street, afraid of meeting people. Then I got into alcohol and then I ended up being prescribed drugs for PTSD. I was around forty-six. When they took me off the medication for PTSD, my mind exploded with stuff from my childhood, the army, and violence—It was just suicide in my mind’s eye.

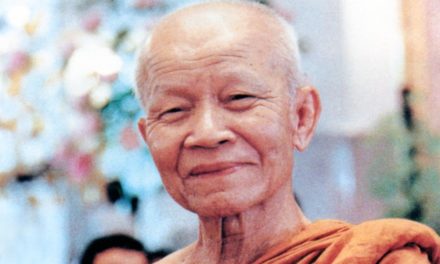

What I tell you now is absolutely true: I left the treatment center, because they couldn’t treat me anymore, and went back to Liverpool, and I was having bad withdrawals. In the bedroom where I used to hide with the curtains closed, I had a television and the remote control was on the bed. I moved and switched the television on by accident, and who’s standing there but Ajahn Sumedho! I didn’t know who he was, but I thought, “I’ll watch this,” because I’d always had this feeling about Buddhism for some reason.

The film was called The Buddha Comes To Sussex. And that was it. I wrote the producer, they then sent me the address of Amaravati, and I phoned them up. I know now but didn’t know at the time that it was Ajahn Amaro, and I spoke to him and I said, “Look, I’m agoraphobic and have bad mental health problems. Can Buddhism help?”

And he said, “Sure. Come down here and stay.”

“How much?”

“We don’t charge.”

I said, “You’re going to help me, and you’re not going to charge?”

“Yeah.”

And I said, “I just don’t believe it.” And that was it, hook, line, and sinker.

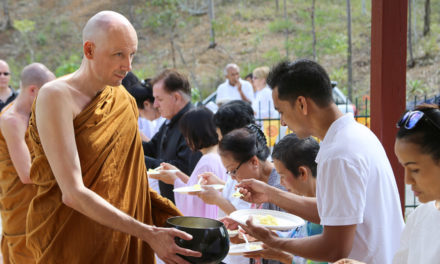

I got one of the lads that worked for me to drive me down, and I stayed there for ten days on retreat. After about four or five days, my head was racing. I couldn’t stop thinking, so I asked the retreat leader—which happened to be Ajahn Attapemo—to speak with me.

He said, “Okay,” and at half-past nine that night, I met him in the hall.

He was sitting there looking very smart—like a leader—and I said to him, “Excuse me Bhante, I have these thoughts in my head, and they just won’t go. What can I do about them?” And he didn’t say anything. He just looked straight ahead. I thought he hadn’t heard me or didn’t understand my accent, so I said it again: “Excuse me, Bhante. I have these thoughts. How do I get them out of my head?” And he looked at me again, like he was cross—like I was a failure. I thought he was going to ask me to leave the retreat.

He looked at me, and he said, “You have these thoughts, and you want to know what to do with them?”

“Yeah.”

And he said, “Tell them to fuck off.” (laughs). He said, “Tell them to fuck off. Don’t let them overpower you. They’re only thoughts.” That was it. It was my attitude toward the thoughts that was the problem. That was Ajahn Attapemo. That was thirty seconds. I didn’t need psychiatric counseling for five years. He just got to the point.

How was the monastery?

It was the best thing I did. I read something every day about Buddhism. I always read an hour a day. I had a book called Mindfulness: The Path to the Deathless by Ajahn Sumedho, and in there it talks about obsessive thinking, and that’s how my PTSD was hitting me, because I was obsessed with the past. I don’t know how many times I’ve read that book—maybe fifty times.

Ajahn Sumedho talked about thinking and mindfulness, and that just made sense. It’s your thinking that’s wrong, and you’ve got to address your thinking; practice mindfulness, don’t believe your thoughts, and learn to discipline your mind. It just made sense. The medical profession had not said that to me. No one had, but Ajahn Sumedho did.

I started to have faith. That’s very Christian terminology, but I started to believe that there was a way out of my misery. I started to believe.

I went for a week every month. And I bought a camper van, and I parked outside the gate, so if accommodation was all booked up, I’d just be in the camper van parked outside.

At the monastery, I did a lot of building work with the Sangha. Amaravati was in its infancy and it needed a lot of building work, so I’d go down there a week, every month or sometimes longer. I enjoyed it. They’d tell me if it needed maintenance work and things like that.

I was meditating every day. I had meditation beads which I used. To put it politely, I have serious mental health problems—that’s a fact. But I was able to cope with them with the help of mindfulness.

Did you have a moment of awakening?

Yeah, I did. The only way to describe it is that I’d already been to AA, but I only had a spiritual awakening when I went to Amaravati in 1988. The teaching meant that there was a way out of the suffering, and that everything’s not permanent, and I’m in control of my own destiny—that there was a way out of that 24-hour, 7-day-a-week suffering. Basically, that’s it. I understood what that’s all about. No one gets away with it. What I mean is, I’ve never met anyone who’s 150 years old. It’s as simple as that. Everyone’s got to die.

And the other thing I noticed as well is that whatever the negative emotions say, you do the opposite. If you’re angry, learn to forgive. If you’re intolerant and want to get back at someone, learn to tolerate. If you’re standing in line at the bus station, you have to be patient. Patience, impatience. Tolerance, intolerance. Forgiveness, non-forgiveness. One side has pain and the other does not. That’s what Buddhism was telling me – to practice opposites. All that crap that had been pumped into my head as a kid—all I had to do was practice the opposite. Where there was fear, face it, when I was depressed, lighten up, when my mind was racing, learn to sit down and meditate, and so on.

There’s a terrorist group in the United Kingdom that’s terrorized and killed friends of mine, and I had a lot of hatred towards them. And what I realized was this: If I had been born in the same environment, in the same area that they were born, I would have been a member of that terrorist group. And the hatred for them left me instantly. It gave me an insight into what mettā was about. That hatred inside of me towards that terrorist group, any normal person would have said, “Well, of course you feel that way.” But it was horrible to have inside me—to feel that.

Was there a way you passed the message on?

I used to take monks down to Liverpool to give talks, and it was all free—I paid for it. No one else paid a penny. I wanted to pass the message on, and I think other people gained and learnt a lot. I’d bring Ajahn Attapemo or the nuns down, and I’d rent a hotel function room which held about a hundred people. I was a self-employed builder. This was in the mid-nineties. People initially all said the same thing—they thought it was a money scam, but then they saw how humble the monks and nuns were.

I’ve been a member of Alcoholics Anonymous since 1974—that’s forty-four years. I would talk about meditation at the AA meetings, and the AA members would come along to meditate as well. It wasn’t a substitute for AA, but it was part of the path of the twelve-step program: step eleven. Meditation was a clear way to improve our constant contact with God and clear knowing.

A lot of people loved it. I took some of them down to Amaravati and one of them asked, “Does it cost any money?”

And I said, “No. No money involved.”

“Well, who owns the land?”

“The trust.”

And I could see her thinking—realizing it was something real.

Did anyone notice the practice’s effects?

I remember the lads I worked with saying, “Oh man, you’ve changed. What’s happened to you?”

And I just said, “Oh, I don’t know.”

One lad said, “Are you alright?”

“Yeah, why?”

And he said, “Well, you’re not speeding round, rushing round all the time.”

The gang members and others in AA really noticed a change in me. They said, “The way you’re sharing now… you were just a really angry man in the past.”

I didn’t mention Buddhism—I don’t push things—but I did mention offhand that I’d been going to Buddhist temples, and they said to me, “Whatever you’re doing, keep doing it.”

As to how Buddhism’s affected the way I treated my daughter, one time when she was a teenager, she came up to me and said, “Dad, I’m putting my phone on speaker. My friends won’t believe me. Dad, have you ever shouted at me?”

And I said, “Not that I can think of.”

And, it’s true. I hadn’t realized it until she said it. When she did something wrong, I’d just say to her, “Is that the right thing to do?” I just tried to teach her to have mettā in thought, word, and deed, and that’s it. To feel safe, to feel secure. Even when I split up with her mother, there were no arguments, no fighting; it was just a separation. That was it.

She was pregnant two years ago, and she came down to my flat and started talking to me: “Dad, what religion are we?”

And I said, “What makes you ask that?”

“Well, we’ve got to know how to bring up my daughter.”

And I said, “What do you mean, ‘What religion are we?'”

“Well, we’ve never spoken about religion.”

“You must be joking. You’re twenty-six and I’ve never spoken to you about religion?”

“Yeah.”

And I said, “You’ve just given me the greatest compliment ever. Well, what do you think yourself?”

And she said, “Well, I know you go to a Buddhist monastery. I think I’ll go down the Buddhist path.”

“Well, you do what you want. It’s not for me to push you.”

And I bought her a Sukothai Buddha, which is absolutely fantastic; a lovely Buddha. And she’s got that in her house now. She’s such a lovely girl; she helps others and is a teacher.

In 1988 I came in contact with the Sangha and the simplicity of Buddhism. You might be miserable walking into a room, say you’re looking for happiness, and the monk would just say, “Don’t try too hard. Just practice opposites” (laughs). It’s as simple as that. Misery’s optional. Searching for happiness is like being in bath with a bar of soap; the more you grab at it, the more it just shoots out of your hand! But if you cup it gently, it just happens.