Dawn of the Dhamma: Illuminations from the Buddha’s First Discourse

by Ajahn Sucitto | March 2, 2021

The Pleasure of Release | Ajahn Sucitto

Introduction

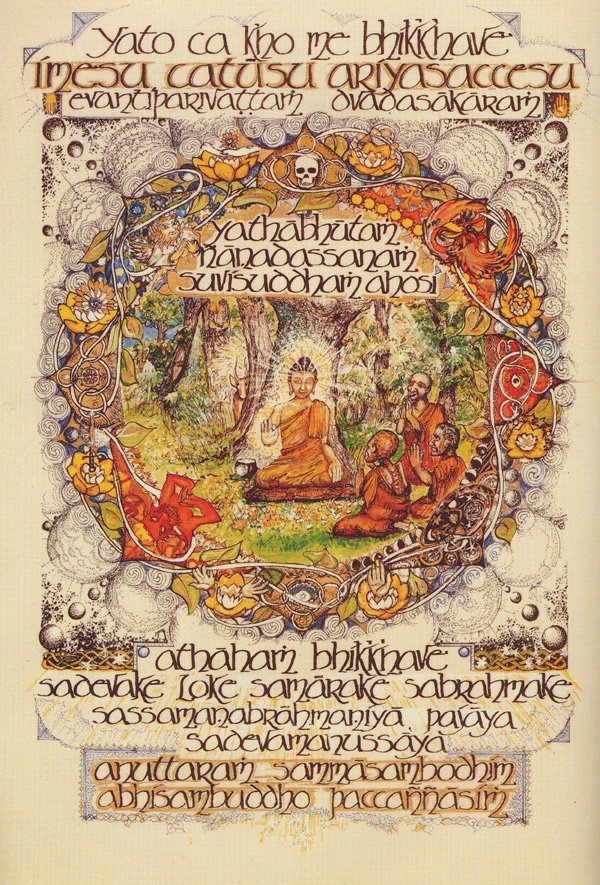

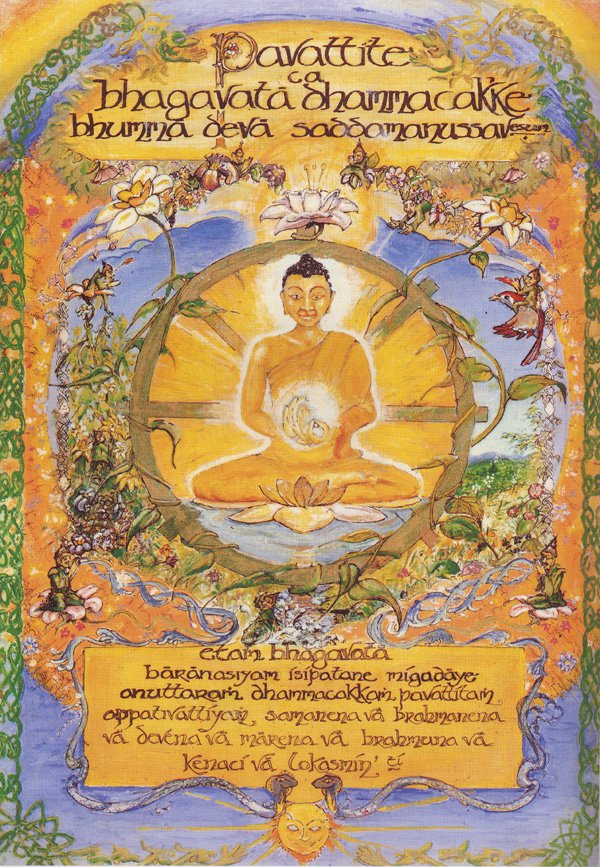

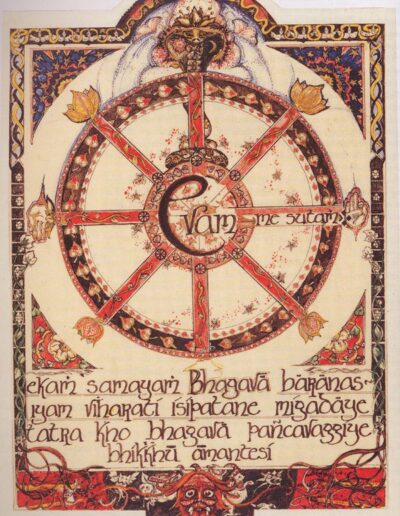

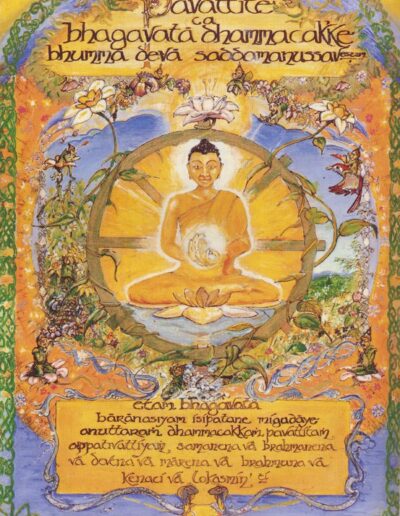

Turning the Wheel of Dhamma (Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta) is a central discourse in the Buddha’s teachings. It is the first full teaching that the newly Awakened One gave, and it sets out the four noble truths and the ‘Middle Way’ – the teaching structure that is the heart of his Way of realization. You can read the discourse in Connected Discourses (Samyutta Nikaya 56).

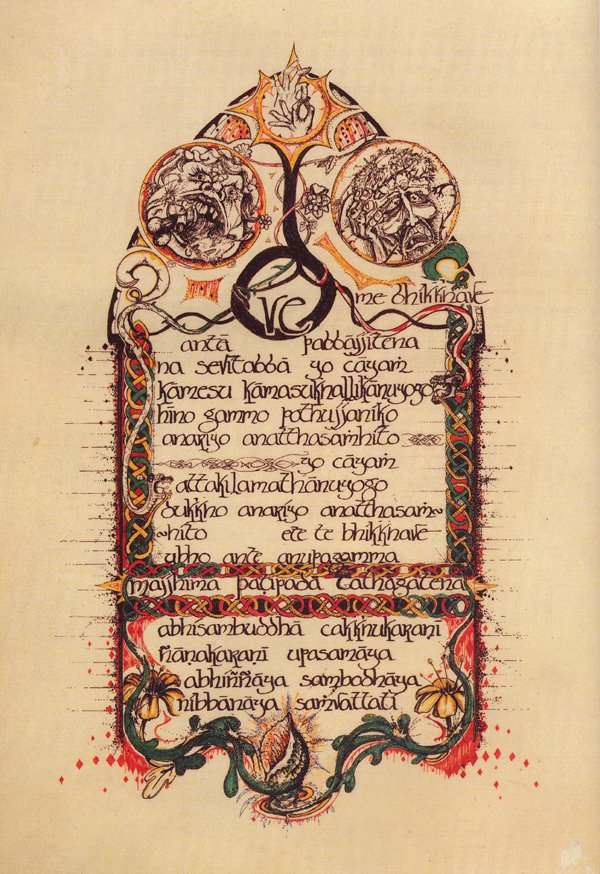

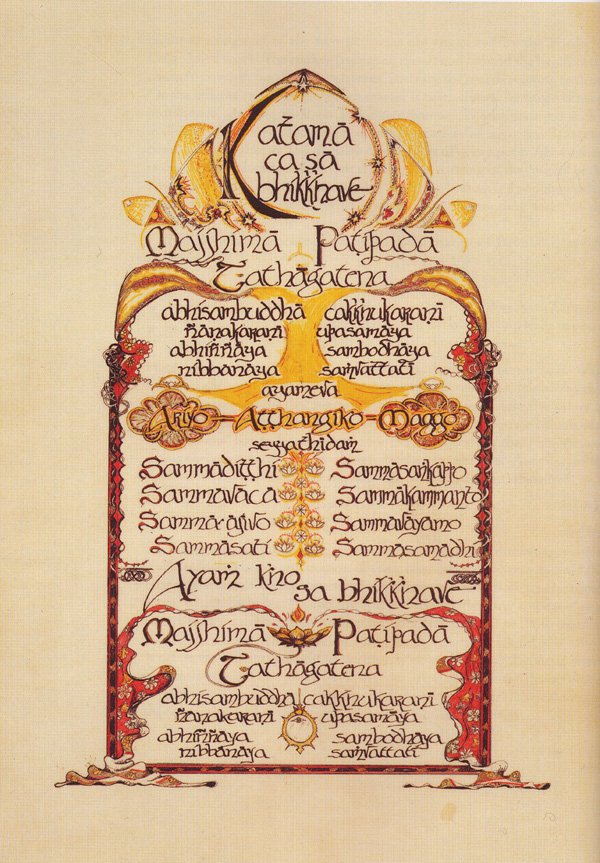

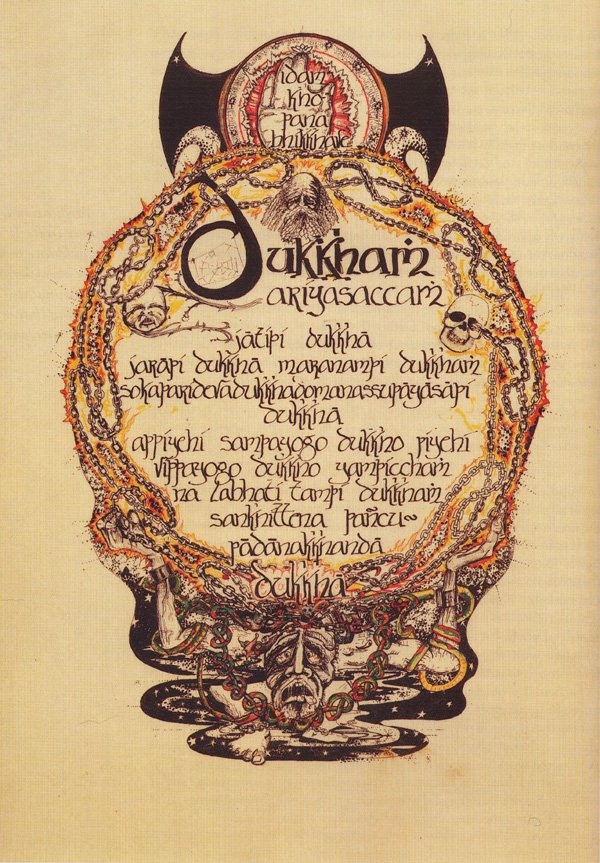

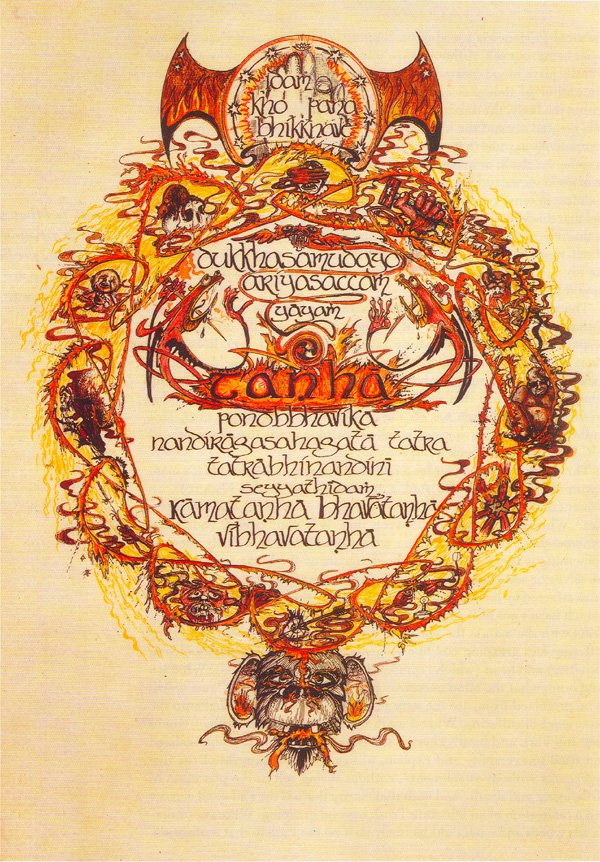

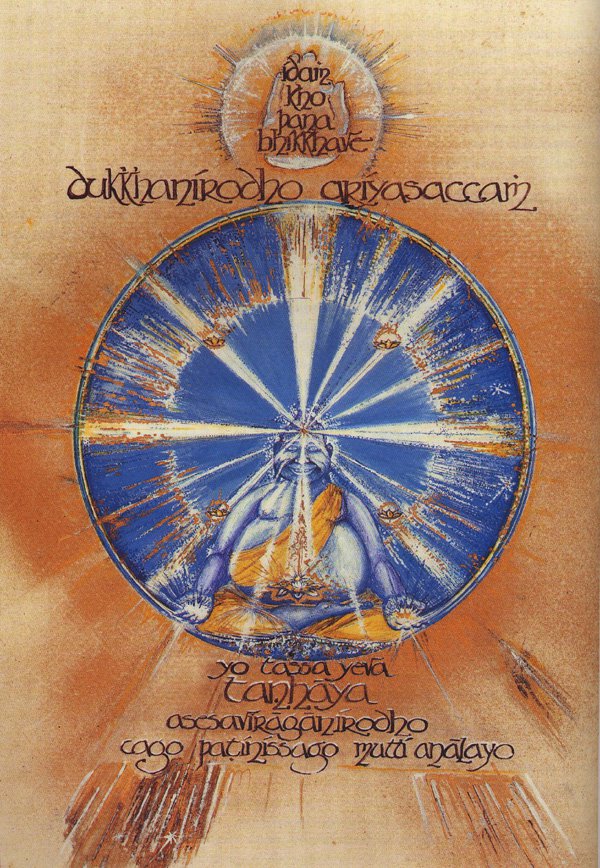

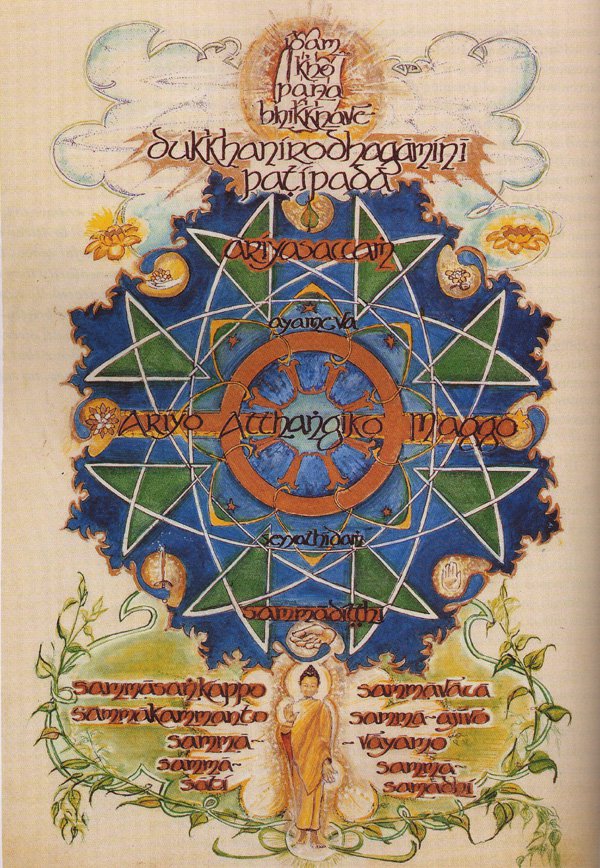

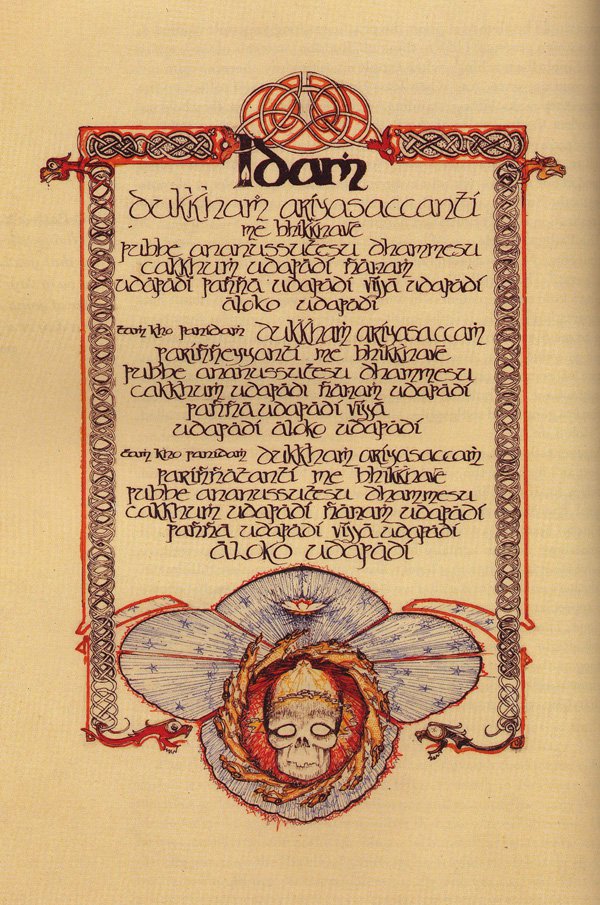

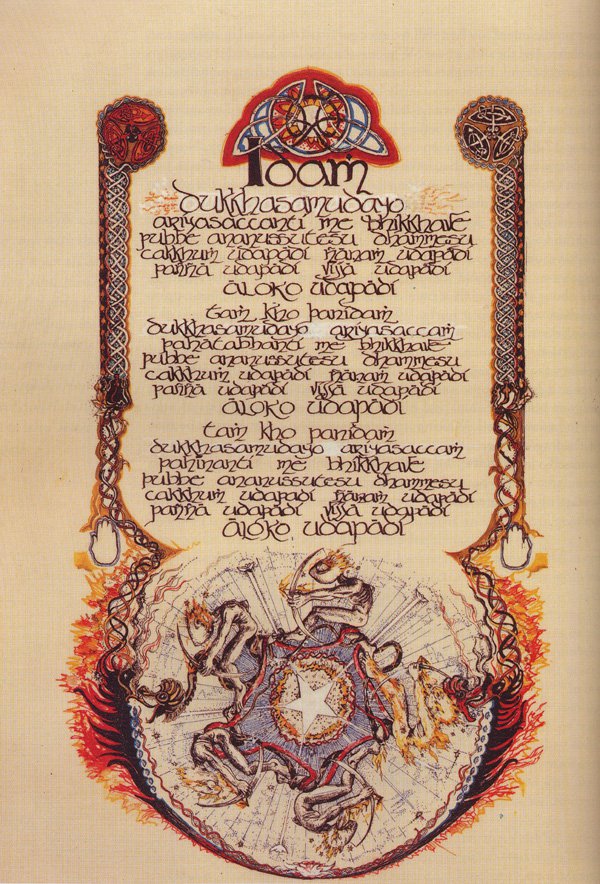

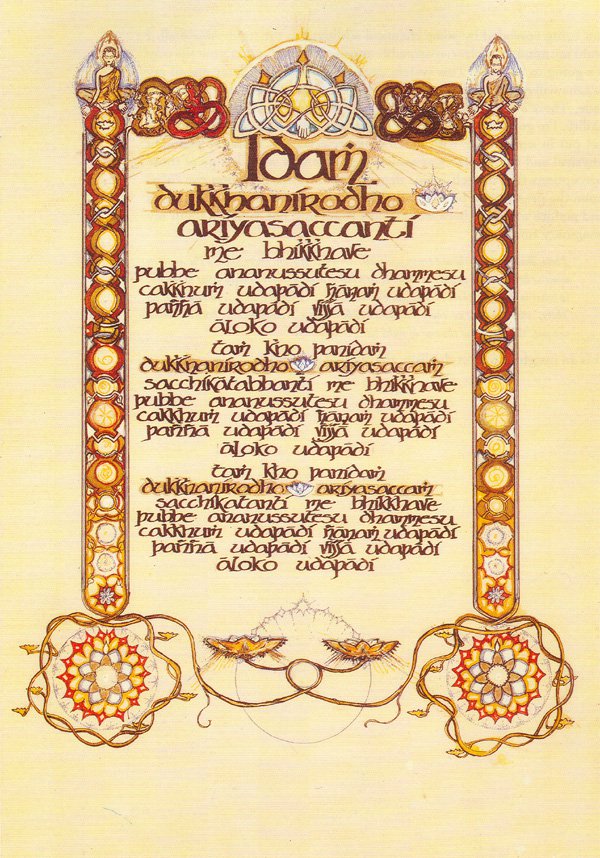

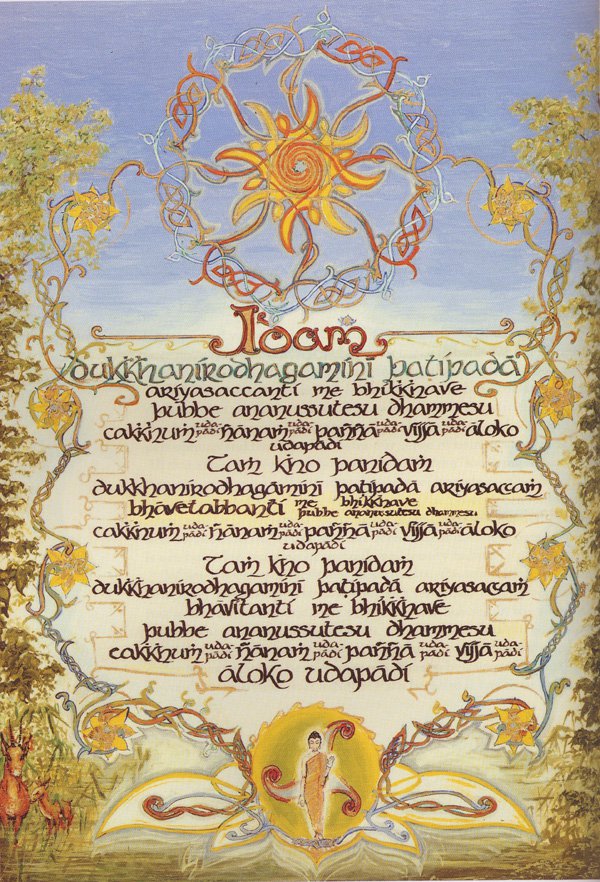

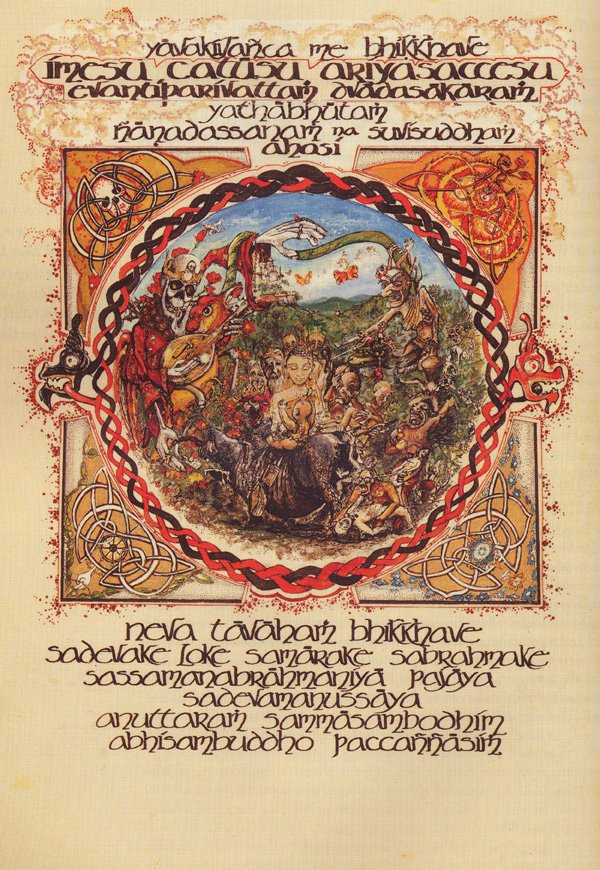

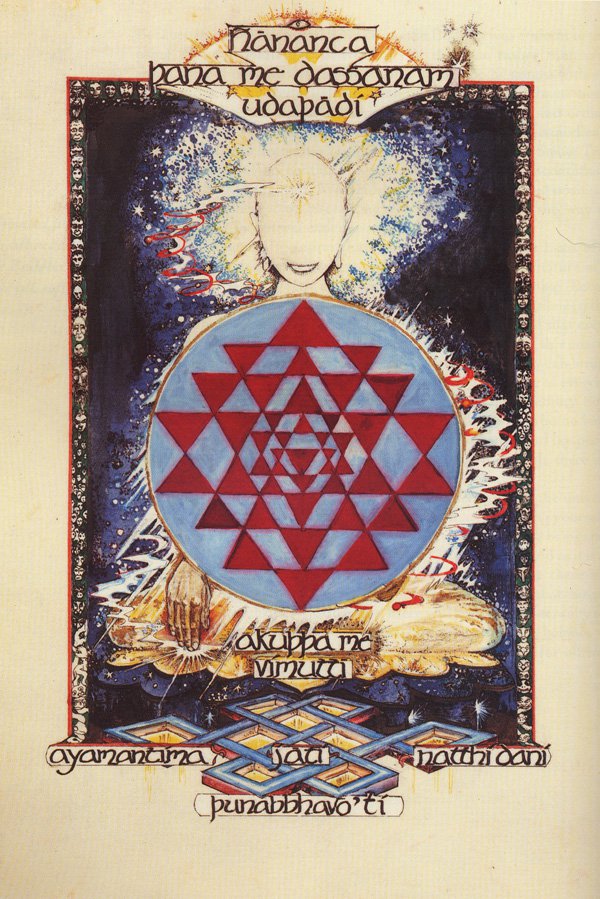

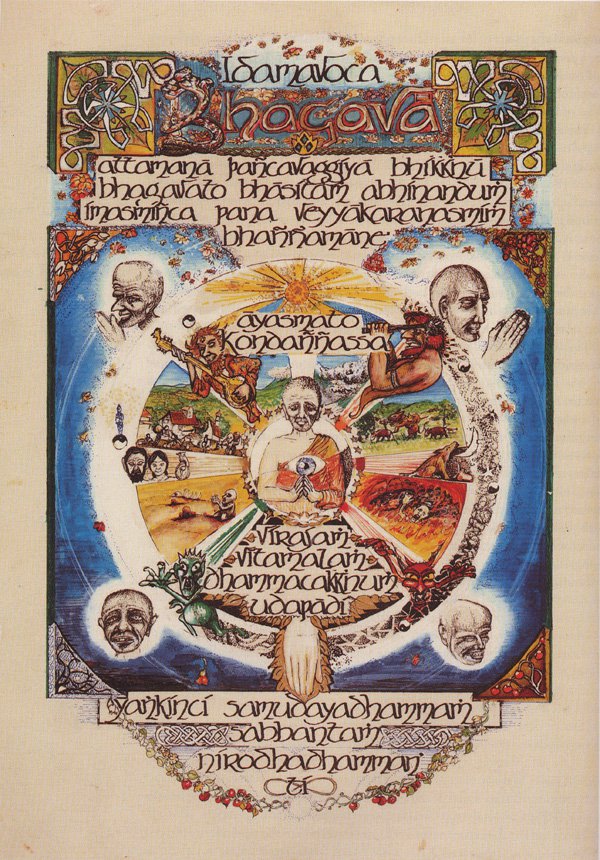

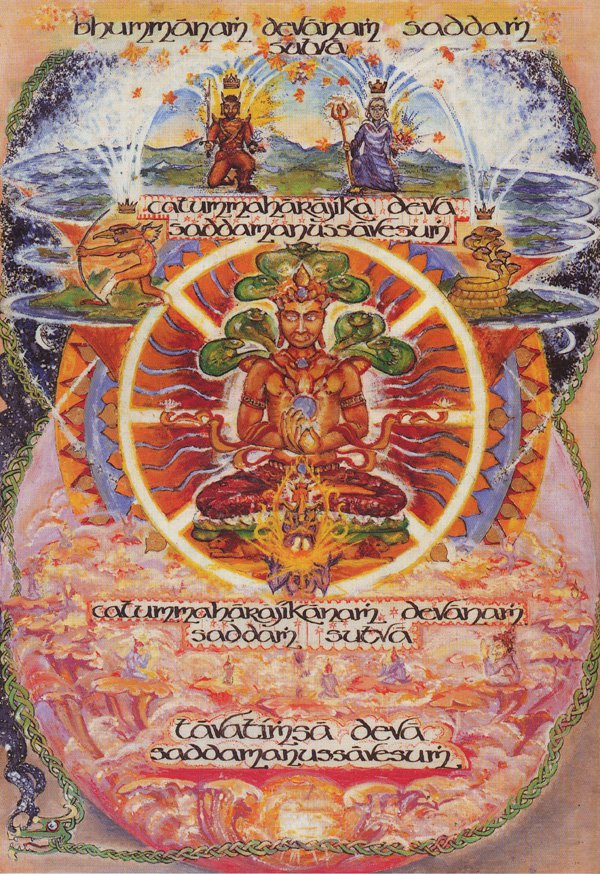

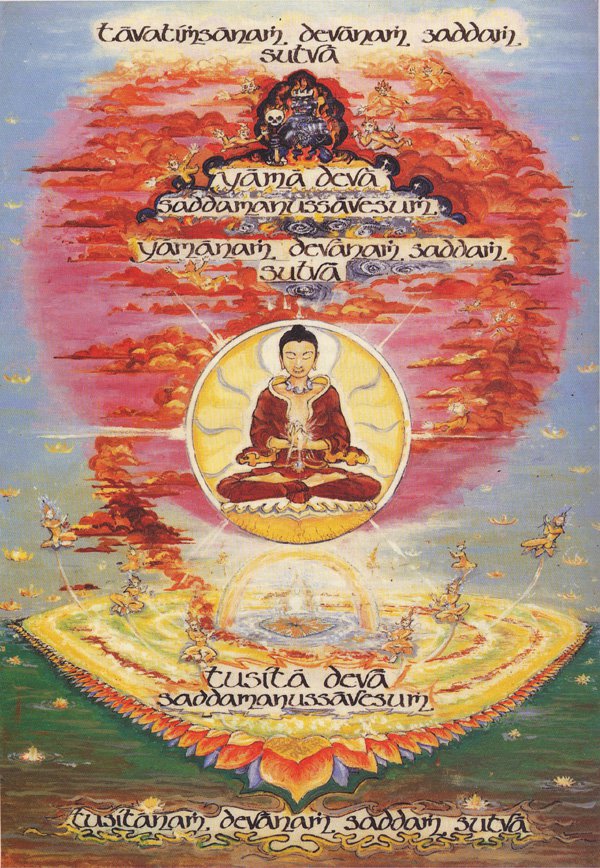

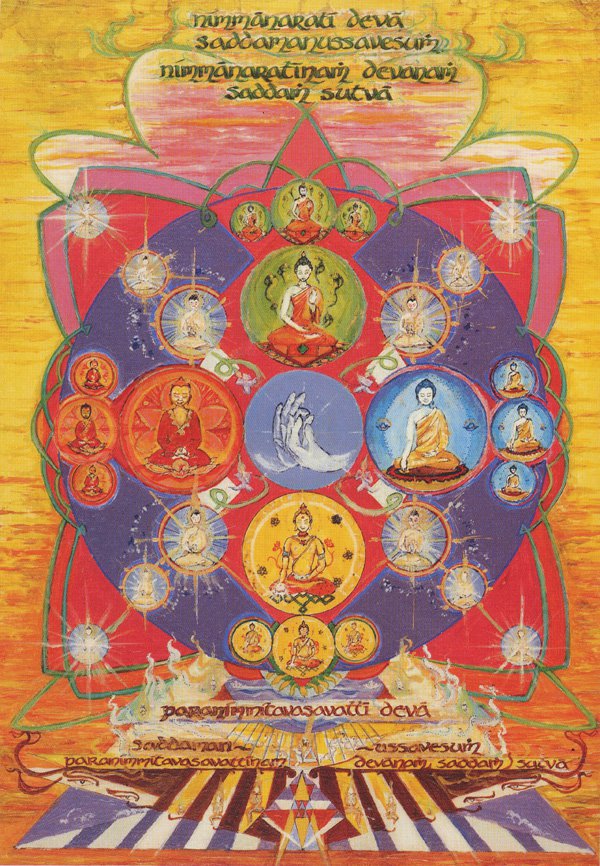

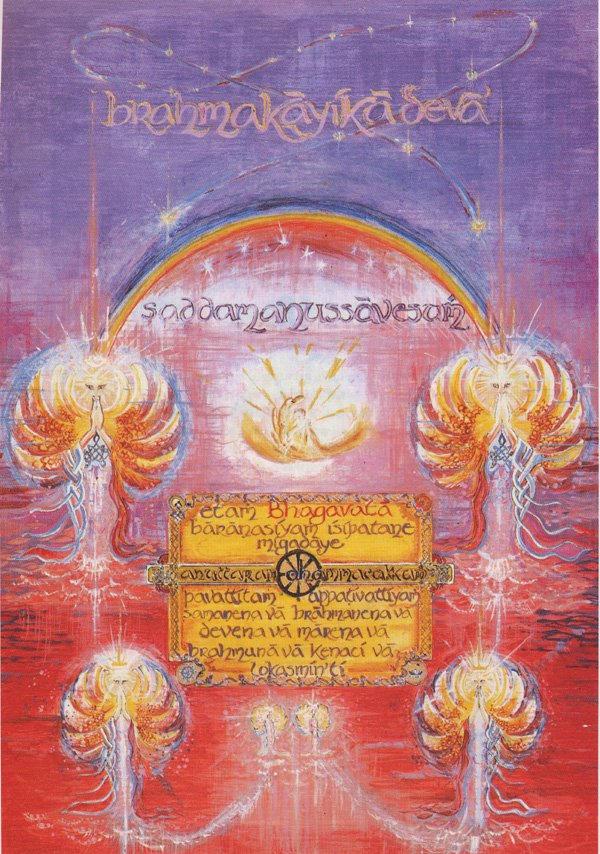

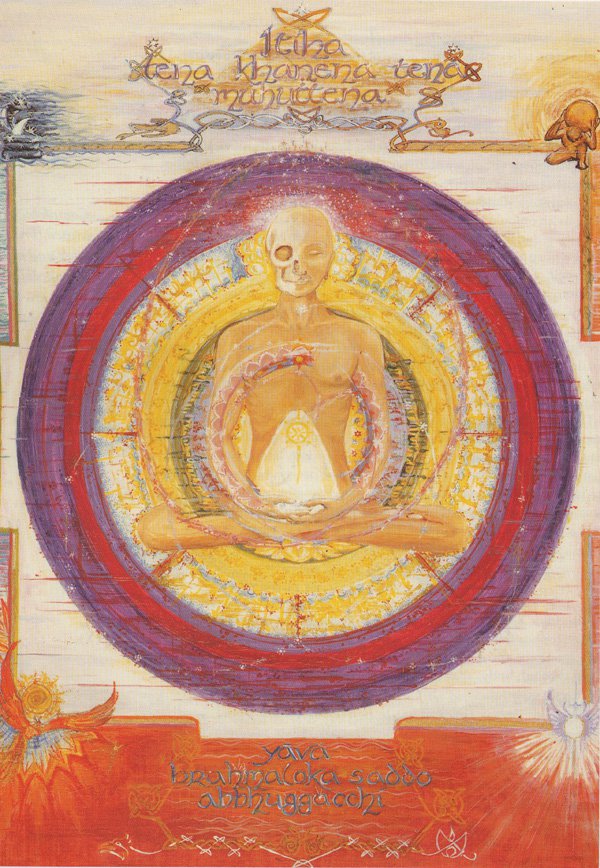

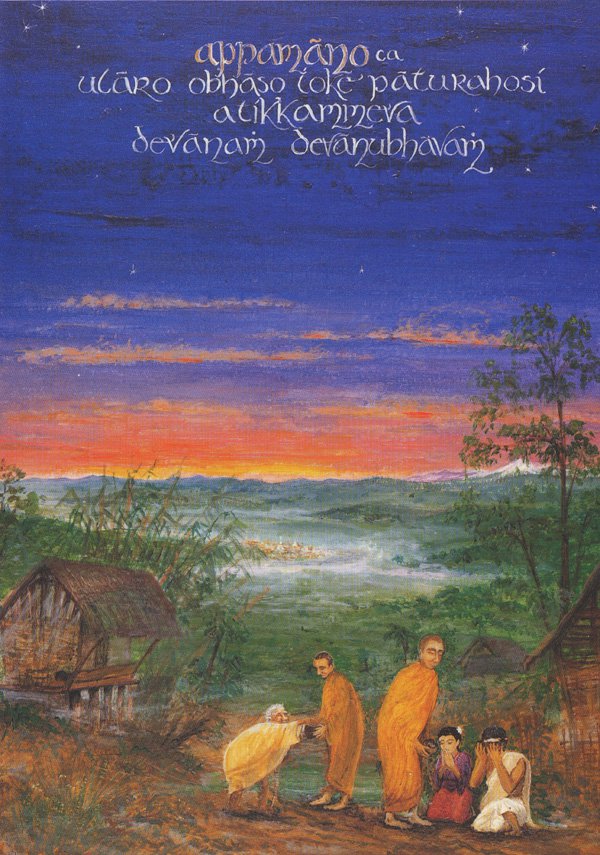

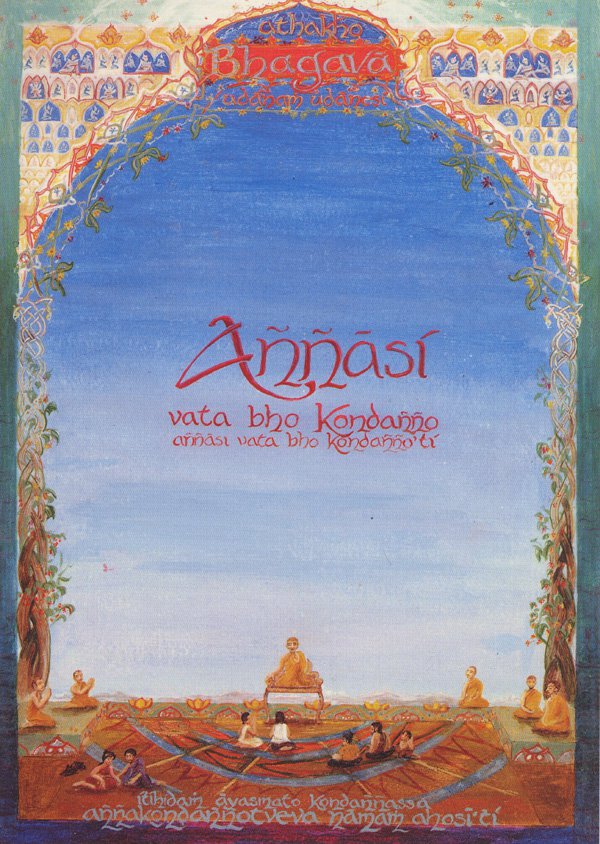

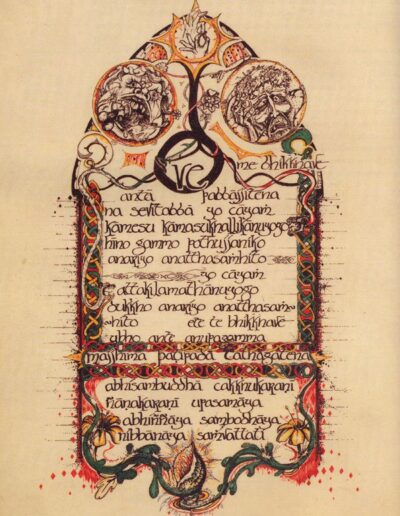

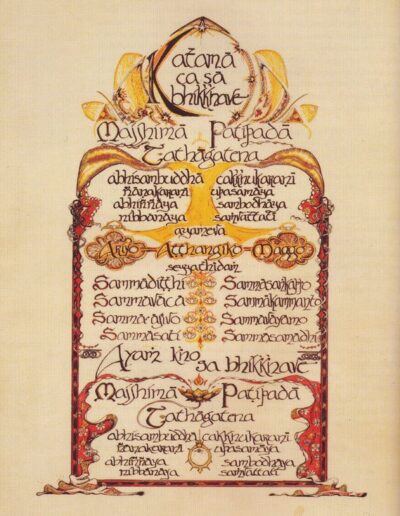

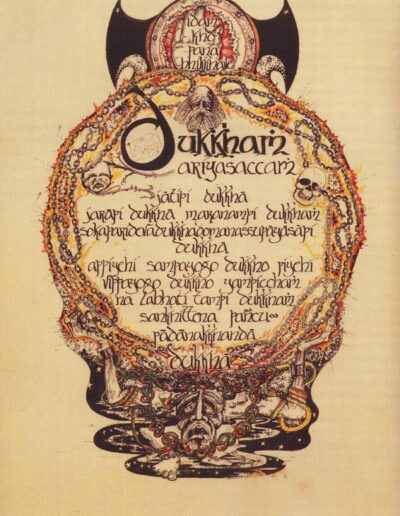

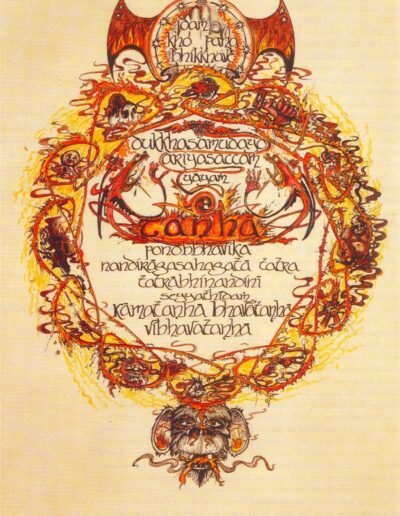

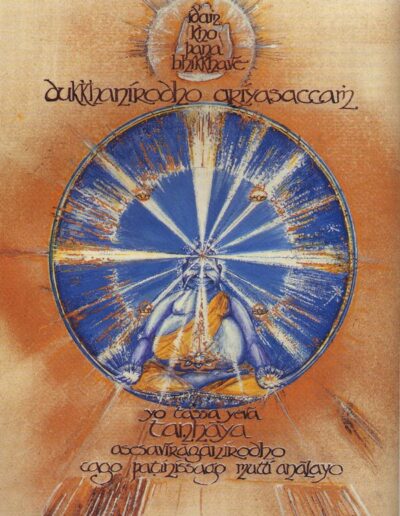

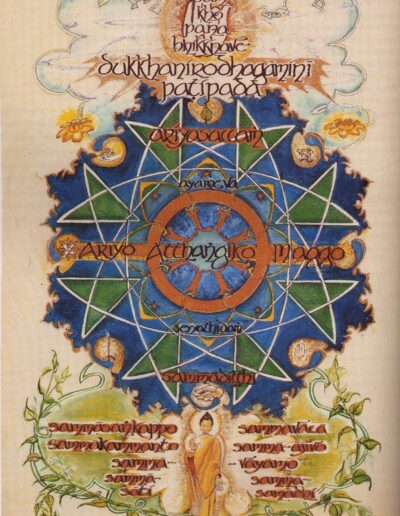

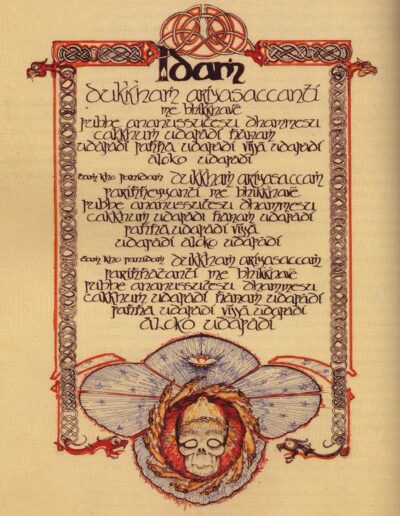

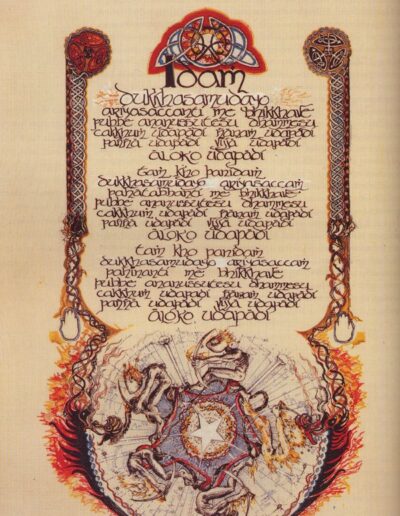

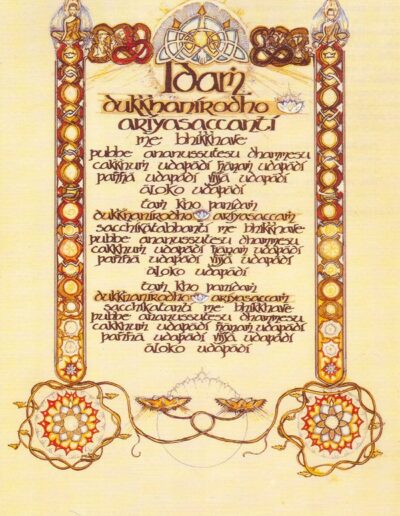

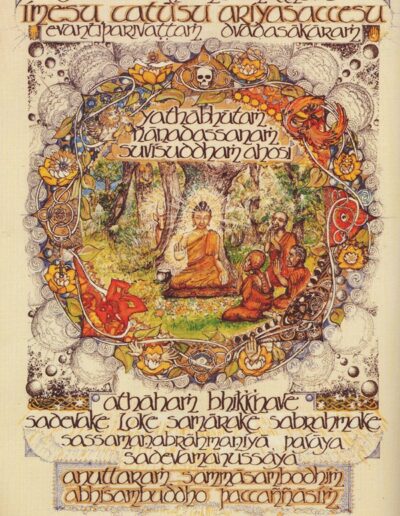

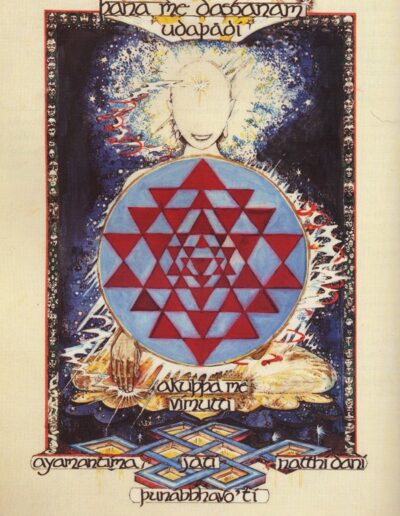

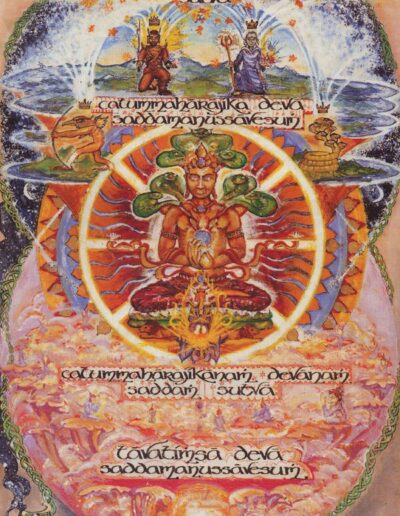

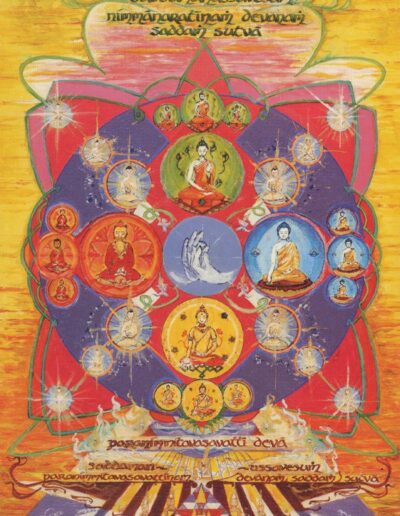

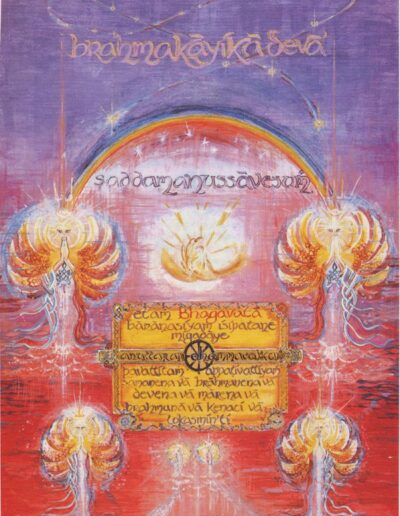

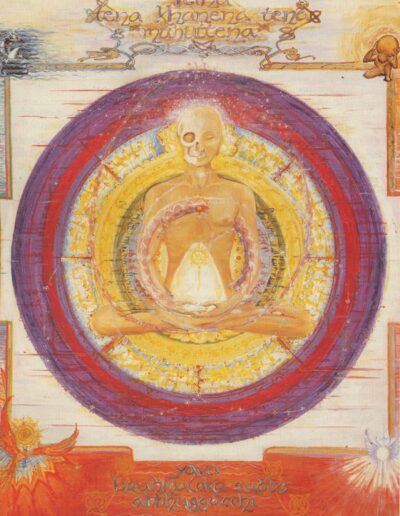

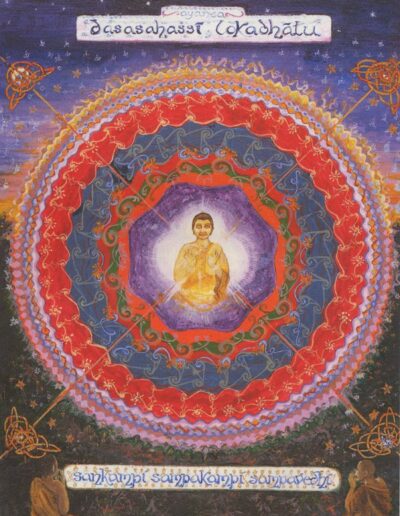

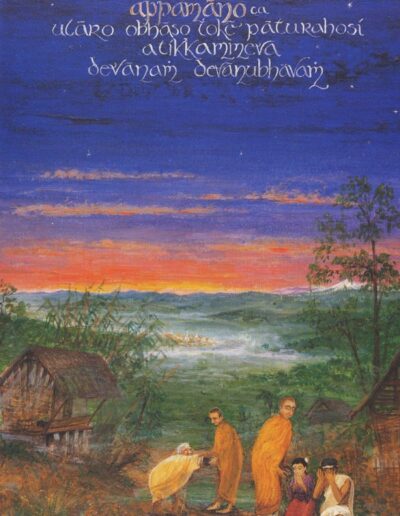

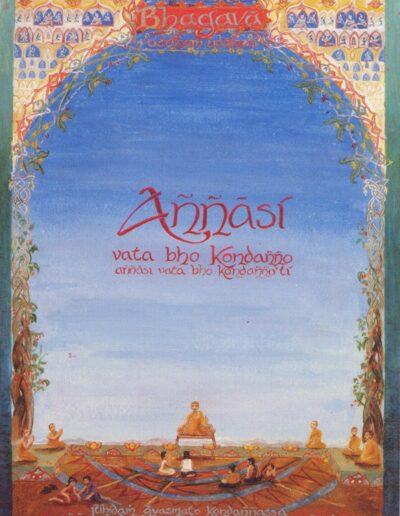

What follows is a series of paintings that I made between 1981 and 1984 that illustrates this discourse… It is presented in the style of an illuminated manuscript in which the words of the text are embellished or surrounded by figurative elements. The viewer will probably note that the style echoes that of an illuminated Gospel in the tradition of the Celtic Church. The knotwork that is predominant in the earlier pictures of the series, and the uncial script throughout, is borrowed from the art of the Book of Kells and the Lindisfarne Gospels. This is a deliberate gesture of respect to the early monastic tradition of Britain, made at a time when I was part of a small Sangha of Buddhist monks (bhikkhus) who had recently arrived in Britain and were engaged in establishing Cittaviveka Monastery in Chithurst, West Sussex. In this ancient settlement, it was very clear that despite the many differences between the traditions, we were inheriting the respect and the place in the society previously held by Christian monks. After selling us the house that became the centre of the monastery, its previous owner excitedly reported to his neighbours: ‘The monks are coming, the monks are coming! Without knowing a thing about the Buddha’s Dhamma, people knew that these ‘bhikkhus’ would be men of peace and virtue, and that was a good thing. In a conservative part of England, the innate respect for a spiritual life granted acceptance to our odd, oriental-styled Sangha. It feels important to acknowledge that.

One of the differences however between the Celtic manuscripts and this series is that the letters themselves are relatively unadorned. This was so that they remain legible and usable as a means of reciting the text – because the series originated out of a wish to present the sutta in a way that would attract the attention of the bhikkhus and encourage them to learn to recite it. As the series evolved, this need fell away and what began as an illuminated manuscript turned into a set of paintings.

Another reason for this shift is due to changes in my contemplative practice. As a beginner my meditation was technique-oriented, with an emphasis on observing a formal structure (such as counting the breath, and ‘noting’ the momentary movements of mind with a thought). You might say it was ‘left-brain linear.’ Over three years, how I meditated became more a matter of feeling and sensing the mind and working in a more intuitive way. So the early pictures are more a matter of line, whereas the latter are more chromatically attuned. In fact for the celestial realms, what arose first in the mind was the chromatic tone that seemed to represent the atmosphere of the deva-loka that was being referred to. This sequence later became the source of a book – The Dawn of the Dhamma – with an extensive accompanying text. This book (from 1991) is now long out of print.

However that book inspired Shambhala Publications to request a revised edition of the text, without illustrations. This became Turning The Wheel of Truth (Shambhala 2010). If you are looking for a more thorough explanation of the meaning of the text, you will find it in Turning The Wheel of Truth. (Editor’s Note: An online transcript of the original book may also be found here).

Finally, what follows is an act of gratitude. When I completed it, I presented the series of paintings to Ven. Ajahn Sumedho as a gesture of my gratitude for his guidance and example as my teacher. Naturally that gratitude extends to the Buddha, to the Sangha that has transmitted this teaching for over two millennia, and to all the people who have supported the opportunity that I have to practise the Dhamma as a bhikkhu.

-Ajahn Sucitto